Detroit Golf Series, Part 2

Rackham, Rouge Park, Chandler Park, and the future of golf in Detroit

In part 1 of the Detroit Golf Series, I looked at the rerouting of Rackham GC, and what a potential restoration of the original Donald Ross routing would look like on the existing property. That project was essentially the impetus for starting this series, but there are a number of different angles at which to look at the entirety of city golf in Detroit.

Detroit Golf Series, Part 1

This is part one of what I think will be a fairly deep series on city golf in Detroit. I have an end goal in mind with this feature, but it would be premature to talk about it at the moment. For now, while I’m still deep in the fact-finding stage, I’ll present this first segment, which is a look at the routing history of Rackham GC. There is a video companion to this piece embedded below.

For part 2, I want to dig a little further into the history of these city courses, with a refresher on some of the recent struggles the courses have faced, and how they weathered the storm to get where they are today.

Rackham

Any real history lesson about Detroit golf has to start at Rackham. With the legacy of a Donald Ross design, Rackham rightfully gets top billing in the city. Even though the original front 9 of the course no longer exists, the 1925 creation by the legendary architect still has a lot of pull, operating as the most successful of the three city courses. “It’s a machine”, as one operator from Troon golf told me.

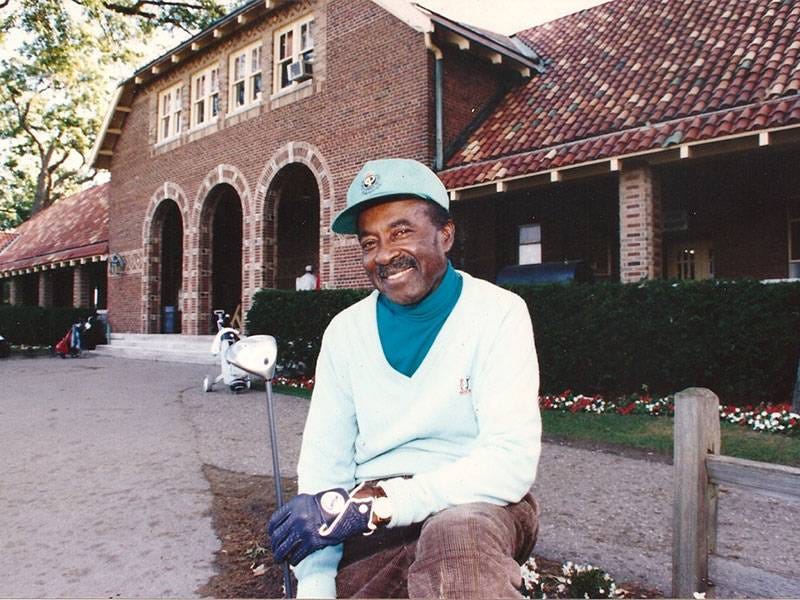

Apart from Rackham’s design legacy, it is further cemented in Detroit lore by its groundbreaking direction under club professional Ben Davis. The namesake of the modern day Detroit Open, Davis became the first African-American head pro at a municipal course in the country in 1952. As the first black member of the Michigan PGA, Davis taught at Rackham for more than 50 years.

A prized pupil of Ben Davis, world-famous boxer and Detroit native Joe Louis, also called Rackham home after catching the golf bug in the 1930s. Throughout the 40s, he hosted the Joe Louis Open at Rackham as an opportunity for the best African-American players to compete, and in 1952, the same year as Davis’ arrival at Rackham, he became the first black golfer to play in a PGA-sanctioned event. Louis’ aggressive press tactics around the San Diego Open that year eventually guilted the PGA into granting him entry as a sponsor-invited amateur.

Rouge Park

While the other city courses in Detroit don’t have the cache of history that Rackham does, a fun little mystery still remains around the origins of Rouge Park. There is a school of thought that, much like Rackham, Donald Ross was behind the design of the Rouge course. To cut right to the chase, this investigation by Laura Herberg of WDET determined that no proof exists that Ross designed the course, and no one actually knows who built it.

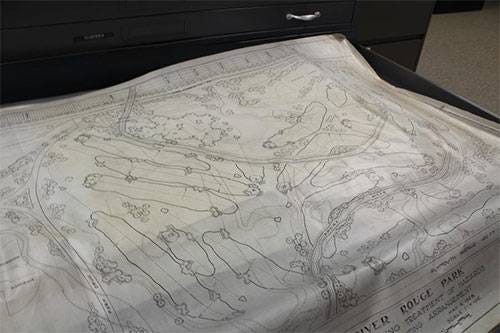

The article did, however, turn up this original routing map:

The plan is unsigned, unfortunately, so we don’t know who to credit it to. I will say that it shares a lot of similarity with the Ross plans that I have studied - Rackham, Detroit GC, and Brainerd (Chattanooga) - from the drawing style to the use of framing bunkers early in the fairways. And as Ray Hearn states in the article, the course is routed in a way that uses the land well. Clearly someone knew what they were doing.

And yet where there is a Ross history, there is usually evidence. That neither the Donald Ross Society nor the Tufts Archives lists Rouge Park as a Ross design suggests that the evidence simply isn’t there. It looks and feels more like someone made a plan in the Ross style, but not Ross himself. Perhaps someone associated with Ross, such as construction supervisor Arthur Ham, who went on to design Arbor Hills and the Country Club of Jackson, created the routing. Or it could simply just be someone who was emulating the designs of Donald Ross.

Regardless of who should receive credit for this plan, the original looks downright intriguing and could perhaps be a target goal for restoration of the course in the future.

I-696 Construction

Before we move into Golf Detroit’s modern day situation, I want to revisit a Rackham question from Part 1 of this series - why was the decision made to reroute the front nine rather than simply making smaller adjustments to retain the routing? The rationale for the new routing, of course, was that the construction of I-696, which cut into parts of the first two holes and shut down the front 9 for several years around 1982 or 83, necessitated the changes. My argument in Part 1 is that the course had enough width and available space to allow the original routing to remain the same, with only slight alterations.

Some further digging into the matter turned up some information from the Tufts Archives, which indicates that the new front 9 was opened in 1985, and was designed by Jerry Matthews. That doesn’t necessarily answer the question of why the rerouting occurred - and yet maybe it does. The Michigan portfolio of Jerry Matthews is massive, containing not only hundreds of original designs, but just as many redesigns and renovations. In 1985, with the design trends of that time and the reputation of Matthews as a renovator of golf courses, it almost makes sense that his response to the 696 construction would be to put his stamp on the course by adding several new holes of his own.

Unfortunately I am not alone in my opinion that, in addition to not fitting cohesively with the back nine holes, the front nine holes lack much of their character, as well.

Troubled Times

From 2011-2018, total rounds played at Detroit’s four public courses, which at that time included Palmer Park, decreased by 21 percent. From 2015-2016 alone, revenue dropped 22 percent. Things came to a head in 2018, as the city faced a critical decision around their municipal golf courses.

To aid in their decision-making, the city contracted the National Golf Foundation (NGF) to conduct a study on the four properties, and recommend a path forward. The resulting 152-page report turned up numerous problems at each location. Until 2017, the courses were managed by a company under a short-term contract. The result was a lack of investment leading to dying greens, bunkers crowded with weeds, poor drainage, flooding, worn-out clubhouses and pavilions — and a sharp drop-off in golfers. NGF estimated that a $15 million investment would be needed to rescue all four courses.

Angie Hipps, the contract manager for Detroit’s General Services Department who oversees the city courses, along with the city council, was tasked with taking this NGF information and charting a path forward. Their first order of business was cutting their losses with Palmer Park.

“[Palmer Park] hasn’t made money in quite some time, and we didn’t think it was worth investing money into it,” Brad Dick, the director of Detroit’s General Services department, told Crain’s Detroit at the time. “We’re post-bankruptcy and looking to be fiscally responsible.”

After cutting Palmer Park loose, Hipps, previously the first female greens superintendent in Michigan, working at Rogell Golf Course, a former city golf course, from 1989 to 2005, before the venue closed in 2007, saw an opportunity at the other courses to implement less drastic, more cost effective changes. “Most of the problems could be solved with basic agronomy practices,” she said. Getting the right turf professionals in place was key to saving the city courses.

That’s not to say that the remaining three courses weren’t under consideration for the same fate as Palmer Park. Upon NGF’s recommendation, the city sought out a management contract with North Carolina-based Signet Golf Associates in March 2018, but the plan needed to be approved by city council. Were the vote to fail, according to Director of Operations for Golf Detroit, Karen Peek, “there was an immediate conclusion that the alternative was ‘we’re going to close the golf courses.’”

Although the initial vote deadlocked at 4-4, a tie-breaking ninth vote a week later cleared the way for a “bridge contract” with Signet, initially running through 2020.

After acting upon NGF’s recommendation to hire Signet, the city also invested $2.5 million for capital improvements. It was Peek’s responsibility, at that point, to allocate those funds where they were needed most - hiring staff, leasing new golf carts, buying new maintenance equipment, aerification and verticutting of greens, maintenance of the rough and bunkers. While simply a short-term fix for many of the nagging issues at each of the courses, it did bring some stability and general improvement to the upkeep of the courses.

The full contract for Signet’s management of the city courses ultimately lasted until 2024, when a new partnership began with Troon golf. “I’m so excited about this new partnership and for Troon to build upon the foundation Signet and Angela Hipps set,” said Crystal Perkins, director of City of Detroit’s General Services Department. “These three golf courses are city gems that have extensive history and hold a special place in the heart of golfers in Detroit and beyond. We believe this partnership will continue to grow the love for this game in our great city.”

Improvements Under Signet

By all measures, the management term of Signet was successful, resulting in an uptick of golf traffic, revenue, and reinvestment in the courses. Karen Peek details some of the changes from the initial Signet contract, starting at Chandler Park.

“This has really been an exciting development over the last year and a half,” Peek said in 2020. “It’s been a real partnership with the city. They have invested in all three properties. It starts when you come in. If you look around [Chandler Park], you see all the boundary fencing was replaced, so completely through the park, around the neighborhood, the expressway [I-94] and north on the Dickerson [Road] side. It really gave a fresh, clean look to the course.”

In the Chandler Park clubhouse, “we have new flooring, new furnishings,” Peek says. “Lisa built the bar. We’re making some improvements to the pavilion area so the golfers have additional space now to sit down either before, during or after a round, have a burger and a beer.”

“Maybe the biggest project here was the installation of a new, fully automated irrigation system. That’s really the lifeblood of a golf course — being able to manage your water, maintain the turf — so that was a huge project.”

Rouge Park, located on the west side, has undergone some marked improvements as well.

“There are six bridges at Rouge Park — they were probably the original bridges — so all of those were repaired and replaced,” Peek says. “The wood that you see on the bar area [at Chandler] is actually from the [Rouge] bridges. It’s a pretty cool story. We’re building some new tees. … We’ve done some irrigation work there as well, drainage work. We’ve built a brand-new pavilion at Rouge Park. It seats up to 100 people; it’s fully enclosed. That’s something they desperately needed because [the] clubhouse is very, very small.”

In addition to the recent irrigation work at all three courses, new investments for 2025 include a new golf cart fleet, and a new package of maintenance vehicles.

What is the vision for the future?

As golf architecture enthusiasts and champions of the game, what do we think the future holds for these properties, and what direction would we like to see them headed in? The survival of the courses after some dire straits and the general improvements made since then are admirable. But going forward, what is the overall vision for the courses? Is just surviving and existing enough? Or can we take a cue from other municipal courses around the country and create spaces that are more inclusive of golfers and non-golfers alike, more adaptive, and more sustainable for the future?

Let’s start with Rouge Park, which has perhaps the most overall potential. It is the only city course with a driving range, for one. Being on the west side of the city, the Rouge driving range is quite a ways away from the other city range option, Belle Isle Golf Range. In addition to driving revenue for the city, the range at Rouge could also serve as a true headquarters for organizations like the First Tee that help kids learn the game. And with the original routing of the course intact, it’s a prime opportunity to restore the appeal of the course with more width and enhanced sustainability practices around the Rouge River, highlighting golf as a good neighbor in the community.

Chandler Park, a course that “does well” according to a Troon golf representative, is the closest to the city, and as a shorter course, serves a key market for youth golfers, women, and other shorter hitters of the ball. Does anything need to change with the course here? That’s tough to say. With two other regulation courses in the city, Chandler Park could be the best positioned to offer an alternative golf experience in the city. Perhaps a nine-hole course, plus a short course? Many cities have converted some of their less desirable golf properties into multi-use facilities with short courses, putting courses, and lighted facilities for nighttime golf. With its flat property and proximity to the city, Chandler could be a prime candidate for bringing that experience to Detroit.

And lastly, the most obvious opportunity is at Rackham and its Donald Ross golf course. It’s also the most obvious challenge. As Detroit’s “premiere” municipal golf facility, and highest-grossing, any attempts to shut the course down, even partially, for upgrades will likely be met with great opposition. The only payoff on offer for such a shutdown would be having one of the, I don’t know, ten best municipal golf courses in the country? Or having a tourist attraction in a golf state that brings in over $1 billion from out of state golfers per year? Some short-term pain could result in an incredible amount of long-term gain, and true stability for Rackham’s future.

Coming up in Part 3, I will take a look at what developments have been taking place around the country with municipal golf, mostly led by public-private partnerships and nonprofit entities. It begs the question - does Detroit need a nonprofit golf advocacy organization to help the city maintain its courses and create a long-term future vision for golf in the city?